Latest News

Alibaba Awrang, left, with family and friends at the opening of his show at The Good Gallery in Kent on Saturday, May 4.

Alexander Wilburn

The Good Gallery, located next to The Kent Art Association on South Main Street, is known for its custom framing, thanks to proprietor Tim Good. As of May, the gallery section has greatly expanded beyond the framing shop, adding more space and easier navigation for viewing larger exhibitions of work. On Saturday, May 4, Good premiered the opening of “Through the Ashes and Smoke,” featuring the work of two Afghan artists and masters of their crafts, calligrapher Alibaba Awrang and ceramicist Matin Malikzada.

This is a particularly prestigious pairing considering the international acclaim their work has received, but it also highlights current international affairs — both Awrang and Malikzada are now recently based in Connecticut as refugees from Afghanistan. As Good explained, Matin has been assisted through the New Milford Refugee Resettlement (NMRR), and Alibaba through the Washington Refugee Resettlement Project. NMRR started in 2016 as a community-led non-profit supported by private donations from area residents that assist refugees and asylum-seeking families with aid with rent and household needs.

This is also not the first time two men have shown work in Connecticut together, as they both recently exhibited at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury in an exhibit curated jointly by The Boston Museum of Fine Art, The Munson-Williams Proctor Arts Institute, and The Mattatuck Museum, which was on display from fall 2023 through spring 2024. The exhibition covered topics of diaspora, immigration, and displacement across the 20th century, including the Jim Crow-era Great Migration, the plight of American Indigenous communities, as well as leading up to the international refugee crisis of the modern day. As the U.N. reported in 2023, “Afghan refugees are the third-largest displaced population in the world after Syrian and Ukrainian refugees.” Awrang and Malikzada, who both have young children, found themselves and their families whisked away from Kabul, the large capital city in the eastern part of the country, by the United States as chaos erupted following the Taliban’s takeover in August 2021. The surge in instability and insecurity, as well as the threat of violence in Afghanistan, propelled their separate evacuations.

Malikzada’s pottery, beautifully adorning the front windows of The Good Gallery, shows off both the craftsman’s extreme precision — this is not the “flaws and all” farmhouse style that has become trendy in the U.S. — and his strength in building up large, voluminous vases that finish on a delicate neck and slightly curved opening. As The Museum of Fine Art in Houston wrote, “Matin [has] revitalized a nearly lost art of symmetrical design and turquoise glaze derived from natural pigments unique to Istalifi pottery.”

One of the most striking pieces in the show by Awrang is “Pomegranate Blood,” which infuses the mediums of acrylic paint with watercolors and gold leaf to create an arresting blend of fiery colors and ornate textures woven into the paint like a poem. As the master calligrapher wrote in the show notes, “Kandahar [an Afghan city on the Arghandab River] is one the provinces of Afghanistan where pomegranates are famous for their sweetness. It is a time of celebration. When I was in Kabul, we had pomegranate parties every year at the house of a dear friend. For this reason, I see the pomegranate as the heart of all and it is blood sugar.”

The show notes provide a journey for gallery viewers as they can travel from the Japanese ink painting “Through The Ashes and Smoke,” noted as the last calligraphy piece Awrang did before leaving Afghanistan in 2021, up to more recent 2024 paintings like “Fall,” a mix of intense pinks and blues that serve as his interpretation of the autumnal New England serenity that yearly envelopes the town he’s come to call his new home.

Keep ReadingShow less

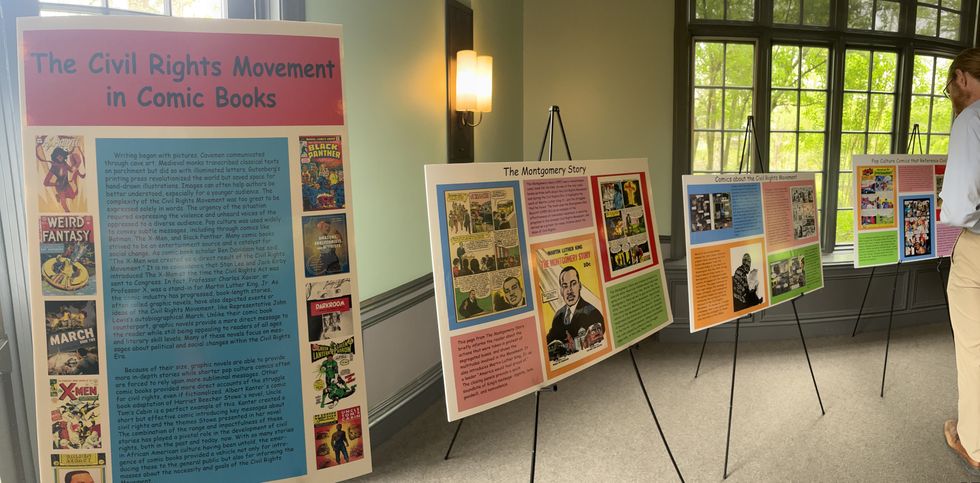

Students presented to packed crowds at Troutbeck.

Natalia Zukerman

The third annual Troutbeck Symposium began this year on Wednesday, May 1 with a historical marker dedication ceremony to commemorate the Amenia Conferences of 1916 and 1933, two pivotal gatherings leading up to the Civil Rights movement.

Those early meetings were hosted by the NAACP under W.E.B. Du Bois’s leadership and with the support of hosts Joel and Amy Spingarn, who bought the Troutbeck estate in the early 1900s.

Students from Arlington High School in LaGrange, New York, Kara Gordon, Nicolas Giorgi, Justin Meneses Aquimo, Akhil Olahannan, and Sheik Bowden together with their teacher Robert McHugh, made the historical marker possible by pursuing a grant from the Pomeroy Foundation.

“We believe strongly that markers help educate the public, encourage pride of place, and promote historical tourism,” said the foundation’s research historian and educational coordinator.

The ceremony began with a land acknowledgement by students Kennadi Mitchell and Teagan O’Connell from Salisbury Central School who gave thanks to the Muncie Lenape, Mohican and Schagticoke people by saying, “This guardianship has brought us to this very moment where we may learn from one another. We honor and respect the continuing relationship that exists between these peoples and this land.”

The crowd was then welcomed by Charlie Champalimaud who, with her husband, Anthony are the current owners of Troutbeck. Speeches were then given by Kendra Field and Kerri Greenridge, co-hosts of the event and founders of The Du Bois Forum, an annual retreat of writers, scholars, and artists engaged in historic Black intellectual and artistic traditions.

Field noted, “It is our genuine hope that the dedication of new historical sites, most especially this one, as part of our larger commitments, will make more complex, more diverse, and more complete the answer to the simple question ‘what happened here?’ and the closely related question, “what might happen next for generations to come?’”

MaryNell Morgan enchanted the audience with her a capella renditions of several of Du Bois’s “Sorrow Songs.”

Du Bois used these songs as part of the presentation of his 14 essays in his seminal work “The Souls of Black Folk,” first published in 1903.

A graduate of Atlanta University where Du Bois taught twice, Morgan sang a medley of songs explaining that the best way to understand “The Souls of Black Folk” is to understand the songs. In attendance at the evening event were also local officials, Amenia Town Supervisor Leo Blackman, and New York Assembly Members Didi Barrett and Anil Beephan. Closing remarks were given by Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Associate Professor at Ohio State University and one of the panelists for the Symposium.

Over the next two days, more than 200 middle and high school students from 16 regional public and independent schools converged to present and discuss their year-long research projects, uncovering the often-overlooked local histories of communities of color and other marginalized groups, answering the questions posed the night before, “what happened here and what might happen next for generations to come?”

Rhonan Mokriski, history teacher and educational director for the Troutbeck Symposium, emphasized the student-led nature of the forum by saying the directive was to “give it to the students and let them run with it.”

Through visual art, documentaries, personal and historical narrative, photographs, and multiple forms of storytelling, students skillfully presented their findings, revealing truths— often difficult ones—in the tradition of their predecessors who did so in the very same location.

Said Jeffries, “It’s one thing if the kids were doing research and then presenting in the, let’s say, school gymnasium, right? But to be able to do it here at Troutbeck, it adds the power of place and makes it all the more powerful.”

Student presentations ranged in topics from the Silent Protest of 1917 and its connection to the Amenia conference of 1916, the links between Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes and Nina Simone, to local families, Amy Spingarn’s quiet activism, reimagining Du Bois’s ‘The Crisis’ through a modern contextualization that included the recent Supreme Court action on Affirmative Action.

Jeffries and Christina Proenza-Coles, a professor at Virginia State University spoke after each set of presentations, responding to and contextualizing the students’ work.

“These projects themselves are commemorations,” Poenza-Coles said. “They are themselves peaceful protests that are pointing us to a more just future.” Poenza-Coles emphasized the interconnectedness of past and present and stated, “Spaces that we would have thought about as white spaces, in fact, were also black and brown spaces from the beginning of history. Histories are completely intertwined.”

Blake Myers, programming, marketing, and culture manager at Troutbeck spoke passionately about the community effort it takes to put on the event year after year. She said that while making sure the program is sustainable, “It really is a replicable model,” and hopes to see other institutions, schools, and foundations adopt it as a teaching tool.

The rooms, walls, and wooded paths of Troutbeck reverberated for three days with stories, past and present, celebrations and revelations of untold narratives and marginalized voices.

Said Jeffries, “America is a product of decisions and choices that were made, and often those were bad decisions and bad choices from the perspective of somebody committed to human rights and to equality. But that’s our foundation, that’s how we started this whole thing.

“So, you have that on the one hand, but then despite the systems of oppression that are designed to do just that, you always have people willing to fight against it and people who are willing to carve out spaces to preserve, promote and protect their own humanity.”

Left to grapple with the complexities of historical memory and its implications for contemporary society, Jeffries offered, “The work that’s being done here, connected with Troutbeck, it’s not just about recovery and discovery, which is critical. But then the question is what do you do with it (the information)? How do we commemorate?

“What do we put in place physically so that we don’t forget. Often, we think about history and this question of ‘if you don’t remember the past, if you don’t remember the systems that are created, then we are doomed or bound to repeat it.’ But we’re not going to repeat anything because most of the stuff, we never stopped doing.”

There was some laughter from the audience and Jeffries concluded, speaking to the students, “But you’re waking up, remembering, focusing, and bearing witness so that we can finally disrupt it. We can finally stop doing the things from the past that have created and generated inequality in the present by focusing on this community that is very much doing the work.”

Keep ReadingShow less

The team at the restaurant at the Pink House in West Cornwall, Connecticut. Manager Michael Regan, left, Chef Gabe McMackin, center, and Chef Cedric Durand, right.

Jennifer Almquist

The Creators series is about people with vision who have done the hard work to bring their dreams to life.

Michelin-award winning chef Gabe McMackin grew up in Woodbury, Connecticut next to a nature preserve and a sheep farm. Educated at the Washington Montessori School, Taft ‘94, and Skidmore College, McMackin notes that it was washing dishes as a teenager at local Hopkins Inn that galvanized his passion for food and hospitality into a career.

Working at Sperry’s in Saratoga, The Mayflower, Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Thomas Moran’s Petite Syrah, Roberta’s in Brooklyn, Gramercy Tavern, then becoming corporate chef for merchandising at Martha Stewart, McMackin learned the ropes from some of America’s greatest chefs. His own culinary jewel, The Finch, so named for the birds that Darwin believed illustrated natural selection through their diversity, opened in Brooklyn in 2014. Ten months later McMackin was awarded his first Michelin star. In March of 2017, The New Yorker reviewed The Finch favorably saying, “. . . it’s the intrepid eater who will be most rewarded.” After closing The Finch, due in part to the pressures of Covid, McMackin became Executive Chef at Troutbeck in Amenia.

This June, McMackin is coming home. He and his team are opening the Restaurant at The Pink House on Lower River Road in historic West Cornwall, just south of the covered bridge. Their opening date is to be announced. Their new space has a stone terrace filled with the sound of the nearby Housatonic River. Michael Regan from Sharon is the Manager. Chef Cedric Durand, a native of southern France will be the in charge of the kitchen. Most recently he was Executive Chef [EC] of Le Gratin, one of Daniel Bouloud’s restaurants in Manhattan. McMackin described his new endeavor:

Our style and techniques are informed by cuisines from around the world, but the lens is very much focused on West Cornwall. The food that will be served is seasonal American food. It’s what makes sense here and now, it’s what we’re able to get our hands on from people close by. It’s casual first and foremost, but it can also be a little dressed up. We want people to feel excited to be with us! The Pink House will be a place for everyone in the community to celebrate, a place to meet friends, a place to feel well taken care of and well fed. The food and drink will be delicious and magical without being precious. It’s a place to go for great food that’s about so much more than the food.

The Creators Interview:

Jennifer Almquist: Tell us more about you as a young person, as a child. What were some of the inspirations that began this passion for cooking food?

Gabe McMackin: So much about this time of year takes me to my origins. Springtime, to listen to new life happen around here, seeing different colors change. I loved seeing things come out of ground. As a little kid seeing what was happening in the garden, getting excited for those first things that I could eat like asparagus, or things that were wild. To make a salad out of wood sorrel and garlic chives, things that were not going to be super tasty, but I could make, was an exciting thing as a little person. Recognizing what different things tasted like felt natural. I liked this thing, I didn’t like that thing as much; this one was bitter, and I didn’t like it at all. I was not manipulating things as much as just tasting them, touching them, feeling them. Appreciating what a raspberry tasted like as opposed to a blueberry, or a wild grape.

As I got older, I seemed to appreciate things less, I stopped paying close attention. I was still sensitive to things and food, but I stopped as excited about it. There were things that came back to me in waves, allowing me to see things in a fresh light. I might think about that in terms of food or in terms of hospitality, and it would affect my perspective.

I got a job in a restaurant washing dishes at the Hopkins Inn in New Preston when I was 17 and learned about how to wash dishes well. That’s the foundation that every restaurant is built on. If you don’t have a happy dish washer, if you don’t take care of your plates well, you can’t really serve your guests well. The rhythm being in that place was infectious.

I liked making pancakes with my father. Making maple syrup was an incredible opportunity to manipulate something from the natural world in an authentic way. Growing something, harvesting something, felt immediate. Later I figured out what it meant to manipulate those things. What it meant to present them to other people. To have people say this is delicious was really satisfying. I felt there a special tool in my toolkit. Sometimes it is a joy, sometimes it’s a compulsion. I must tune this thing. I haven’t been able to make this thing as great as it could be. Does it taste right?

JA: From your elemental experience of a raspberry, do you still seek pure essence in your cooking?

GM: If it doesn’t taste like the raspberry you’re missing that spirit, you’re missing that essence of raspberry. If it’s not there, why is it on the plate? If you are not using something well, you show the ingredient disrespect, plus you’re not using all the magical things available. I love the idea of sticking to what is from here. The food that’s going to make the most impact is going to be the one most full of life.

JA: Is cooking like poetry to you?

GM: Yes, the best words and the best order; it’s the best ingredients with the least amount done to them.

JA: Did you have traditional training in a culinary school? Have you been able to remain yourself, not too influenced by another style or chef?

GM: I’ve been able to work for very talented people. My apprenticeships working with people informed my understanding of technique. Some chefs have palates that have amazed me. The way they think creatively about building flavors and dishes, telling stories in food has been very powerful. The education that I’ve gotten in food, or in hospitality, has not only been from restaurants, but it has also come from the world. I haven’t done culinary school, but I know how to learn. I can turn that magnifying lens on a peach for the essence of that peach. I want to study animal butchery, I want to learn how to fix problems, or build a vinaigrette tolerant of high temperatures.

JA: Tell us about your experience at Blue Hill at Stone Barns.

GM: Stone Barns does things the right way. They have a beautiful system, the practice of making food and caring for ingredients. They look deeply. They’ve created a formula that I don’t think could work anywhere else in the world. To achieve something that is satisfying on so many different levels, intellectually, practically, functionally - it’s something that you would struggle to replicate. The spirit of food being connected in every part of you, the ways that it was sourced, the ways that it was prepared, the ways that it’s been stored, the way that it’s been cooked. I learned to do things on a deep level as a form of respect.

JA: What was it like working for Thomas Moran at Le Petite Syrah in New Preston?

GM: I learned a lot from him about how to cook, how to think, how to move, how to work, both in his system and how to do my own thing. He gave me a lot of positive encouragement and some creative freedom to develop ideas.

JA: What do you find challenging working in a professional kitchen?

GM: There is a switch in my brain that lets me change my pattern when I’m in the restaurant mindset, especially in the kitchen as a cook mindset. I will go to the ends of the earth to make something happen, while in a different environment I have a hard time following instruction. The challenge of being a product of the Montessori education, a deeply ADD person, and somebody who has a problem with authority, it’s hard to have somebody say do it this way and just say yes. I can do that in a restaurant because of brute force. You need to be so clear about what you want, what you need, when you need it, as everything is happening at once. There is different language being used. The sense of urgency is vital and the navigating the forms of communication is intensely challenging.

JA: How do you handle tension in the kitchen?

GM: It is a pitfall that people working in restaurants, over many generations, have fallen into - they’re horrible to each other. We create this pressure for ourselves. Sometimes there is an imbalance between the guest and the host. There must be mutual respect for this type of environment to thrive, for me to do what I love.

JA: It has been said of you that you remain an oasis of calm. How do you maintain that in a busy kitchen?

GM: I ‘ve had good mentors that helped me see the dance for what it is. To know each table has its own rhythm. If you are choreographing the whole dance, each table can be perfectly in sync with the other tables, with the kitchen, with the bar.

JA: Has there been a downside, a dark moment when you were against the wall?

GM: All the time. Closing The Finch was a difficult decision. Covid forced me to make that choice. We did not want to pivot into being a different kind of a space, like a grocery store. Others chose that path to keep the lights on. I did not have the money to put into retooling, and didn’t have the appetite to fight with the landlord I was always in conflict with. Getting a restaurant open is tremendous success, telling the story is tremendous success, yet we hold ourselves to the standard of existing forever and making tons of money. I worked so hard to make that restaurant profitable, that when we shut down it was in some ways a relief. The opportunity to be there was magic.

JA: Were you sad that last moment closing the door to The Finch?

GM: I was one of many people doing that during Covid. Yeah, it’s still very hard.

JA: They say you made something great from nothing.

GM: I took a tattoo parlor and turned it into a restaurant.

JA: As your life moved from city to country, your personal life expanded with your wife FonLin Nyeu and your two sons, Jasper Fox Nyeu-McMackin and Blaise Tyger Nyeu-McMackin. Is it just a different set of pressures living in the country, or can you return to that original boy with the raspberry in his palm?

GM: I get to focus on different aspects of my life. Being in Litchfield County feels like home again. I’m with my family. My father is here, my mother is here, my sisters live nearby. I am renewing old relationships with people who had a big impact on my life. It is different type of kinetic energy I feed off here. I’m happy to have the knowledge and experience of spending 20 years of my life living in New York, but I am thrilled to have my kids go run around in the yard, thrilled to have a stream to wander along, or to just be with people at this pace now.

JA: Your clientele here in Litchfield County will be sophisticated group, but also a different mixture of people. How will your style adjust to not being in the city?

GM: Returning to this place is an incredible feeling and connecting deeply with this audience feels natural. Much of what I am inspired by is from this part of the world.

JA: For the average person, there has been a food renaissance which includes nutrition, the origins of your food, our microbiome, eating local foods, organic farming, composting food scraps, etc. Has your role as chef changed as well?

GM: I think a lot of what I do is teach. Not just how to follow a recipe, or how to build this dish. People come into the kitchen to learn as a part of their journey.

JA: Is it hard to create a team in the kitchen?

GM: You know that person you are training is not going to be with you forever. I would prefer to build a team, provide incentives for people to grow with the company, and commit to staying. It is hard to find cooks, servers, bartenders that want to stay together. I learned that valuable lesson at my first job at Hopkins Inn. To sit with everybody, no matter how deep in the weeds you are, to take the time to really be together as a team.

JA: What was it like to work for Martha Stewart?

As the Corporate Chef for merchandising, I built a line of retail food that we sold through Costco and did projects for the magazine. Martha is one of the magic creatures in the world of making food and lifestyle.

JA: How do you find balance with your personal and professional life?

GM: I took a period of family leave when my newest child Blaise was born. He is going to be two in in August, and Jasper will be 9. I had put a lower priority on making time to be with the kids, and be with my wife, and needed to change that.

JA: Tell us about creating The Finch. You said at the time, “The reason I made this place is not for the recognition. It’s to be a part of a conversation with our guests, with our staff, with all the cooks, with all the people who make or grow or produce the food we use.” Did you achieve those goals?

GM: The Finch was all my own doing, and it was magical. We opened in 2014 and it was everything all at once. Our success required me to apply brute force to what was going on. 8 1/2 months after The Finch opened, we had a baby. Just before that we found out we were getting a Michelin Star, then questioning what it means to get a Michelin Star? I see consistency as a part of why we were given the award. I don’t see it as the origins of our award. I see it as a vote of confidence and as an award for driving an exciting process. I was not trying to be fancy or formal, but because people are gravitating toward us, how do we make this thing make money? Is it impossible? OK, we can try and change these 17 things. It was all wonderful, it was all pressure, which that takes its toll over time.

JA: How did you balance working at The Finch and Troutbeck?

GM: I was doing both things seven days a week. That was hard on me, very hard on my wife and our baby. After closing The Finch, I joined Troutbeck fully. It was wonderful to work in that beautiful space, to be able to tell those kinds of stories, to practice the craft of doing things on a large scale.

JA: Please share with us your farewell to The Finch.

GM: I am overwhelmingly grateful. We have gone beyond what we thought was possible in making this restaurant live. It has been an honor, and we are full of the memories you helped us create. But it is time to close The Finch and find a new path.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading